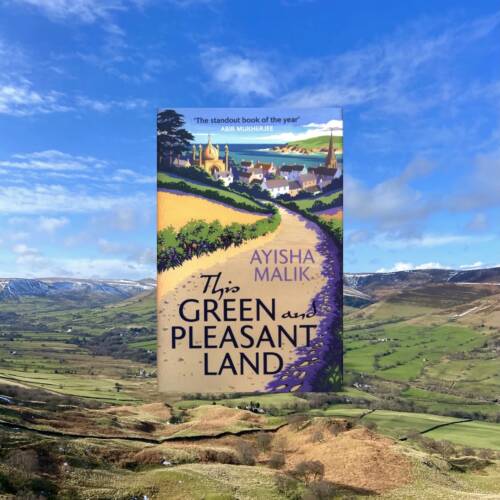

Book Review: This Green and Pleasant Land by Ayisha Malik

02 Mar 2021For the title of her third novel, Ayisha Malik borrows a famous line from the well-known hymn Jerusalem by William Blake, which speaks of building Jerusalem “in England’s green and pleasant land”. This novel follows Bilal Hasham, who is instructed by his dying mother to build a mosque on the rolling hills of his little English village – much to everyone’s (including his) horror. What follows is a slightly rocky and often humorous journey looking at Bilal’s faith, family and belonging in the place he calls home.

The story starts with Bilal’s mother leaving her instructions, after which we get an insight into the comfortable life Bilal and his family have carved out for themselves in their village of Babbel’s End. In the village, Bilal goes by ‘Bill’, rarely prays, enjoys a drink at the weekly pub quiz and shies away from his Punjabi heritage. As the novel progresses, we see that Bilal’s marriage is hanging on by a thread, but we also get to witness his growing connection and understanding of his late mother, and we are treated to heart-warming characters such as Rukhsana Khala, Bilal’s mother’s sister who comes to stay. The backlash and struggle Bilal is faced with because of the mosque proposal triggers both personal and religious growth, bringing strong themes of identity into the novel. This story is more than just one of building a mosque in a community that doesn’t want one – it’s a necessary exploration into what it means to be a minority in modern Britain. The characters are not caricatures of non-practicing Muslims or racist villagers, instead they are the kind of people you meet every day, which makes the story all the more realistic.

What I enjoyed about the novel was that it didn’t pretend that there would ever be a happily ever after. Reading this, you will experience the uncomfortable truth of being a minority, of seeing how you must adapt, always be more gracious, and put up with things others wouldn’t, simply because they’ve never had to. We get to see how Bilal grows in the novel and becomes more confident and unapologetic in his identity, which I found especially comforting to read from a Muslim perspective. The theme of change is very strong throughout the story; many of the characters evolve as people, particularly their understanding of themselves and those around them, and this growth is reflected in the village landscape. The aesthetic of the quaint little British village is threatened by a mosque, mainly because it would serve as a stark reminder of the recent infiltration of an ‘other’, which is an uncomfortable pill for many of the residents, young and old, to swallow. One of my favourite quotes from the book was about reflecting on the past, both the personal and collective: “He [Bilal] wasn’t fond of this historical blame ideology. ‘You can’t move forward if you hang onto the past,’ he added. Vaseem thought about it. ‘No, bro. But you can’t move forward without thinking about what went wrong in the past either.’”

The story felt necessary because it really tried to get to the bottom of issues a lot of us often skirt around. Why did the villagers not want a mosque? Why was Bilal himself initially against the idea? What does assimilation into British society really mean for Muslims and minorities in the UK? We may shed our identity and beliefs in an attempt to assimilate, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that we are not still viewed as the ‘other’. In the novel, Malik questions whether the initiative to build other places of worship would be met with such resistance (“And if someone wanted to build a synagogue, how would he feel about that?”). It’s unclear whether other places of worship would have been met with open arms – it’s likely that there would be opposition to other places of worship rooted in different forms of prejudice. However, this particular part of the story highlighted the intertwining of both Islamophobia and racism in the prejudices we often see in modern Britain; for the South Asian Muslims in this novel, it is both their religion and skin colour that is offensive.

So to truly become ‘British’, must we shed our identity and beliefs, or insist on making our mark on the land we call home? By the end of the book, I realised that Malik is suggesting that it is both of these things – that as Muslims in the West, we have a right to our own spaces, but that comes with a compromise that enables co-existence. Whether this is a fair compromise is up for debate but perhaps for now, this is how things will continue to go.

Overall, This Green and Pleasant Land is an enjoyable book and a good representation of Muslims in fiction. It manages to get you thinking about a variety of relevant issues without being heavy or preachy, and the characters are incredibly easy to grow fond of. Despite the discord unfolding on the streets of Babbel’s End, Malik’s writing manages to keep the story warm and hopeful. There’s anger, sadness, loss and hope, and it’s this perfect mix of emotions that so accurately mirrors the ups and downs of life that makes This Green and Pleasant Land worth the read.