Clashes Over India’s Citizenship Law: A Familiar Face of Hostility for its Muslims

25 Feb 2020The unrest in India surrounding the government’s new citizenship bill has not lost any momentum, as Muslim-Hindu clashes lead to 13 deaths in the Indian capital after protests are met with violence. A mosque has also been set ablaze, reports say.

The citizenship bill was passed on December 11th, 2019, after failing to be passed by India’s upper parliament in 2016 amid widespread political opposition and protests in India’s northeastern states. However, after a landslide victory in the May 2019 elections, Prime Minister Modi’s openly Hindu-nationalist agenda has finally gathered the support for its implementation.

But how exactly does the bill affect India’s population, and why is it so controversial?

Primarily, it is an amendment of India’s Citizenship Act from 1955, which stated that foreigners were able to gain citizenship if they were to live in the country for either seven years (from undivided India) or twelve years from other countries.

The amendment in December 2019 brought religion into the criterion for citizenship. This bill now provides amnesty for 6 different religious groups living in neighboring Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, Parsis and Jains, who are all seen to be persecuted minority groups in the listed countries, are included within the bill. However, Muslims are left off the list.

This move has been criticized by many international organizations and governments as being discriminatory, and contradictory to India’s historically secular constitution. Many political commentators have argued that the amendment unfairly disadvantages Muslims in seeking immigration, and fast-tracks other religious groups to citizenship.

Indian Muslims might also be at risk of losing their property and voting rights, whilst also further marking them as a people vulnerable to discrimination and violence. The Indian National Congress has stated that the bill is an effort to polarize the country and further alienate India’s Muslims.

However, supporters of the bill and Bahratiya Janata Party (BJP) members have responded to its criticism, urging that the listed neighboring countries are ‘Islamist’ ones, and there should be no persecution for Muslims to flee from, as all three of these countries have amended their constitutions to make Islam the official state religion.

But is this really the case? In fact, it has been cited by many that there are multiple Muslim sects that experience discrimination and marginalization in those respective countries. The Hazaras in Afghanistan are victims of constant oppression by the Taliban, whilst the Shias and Ahmadiyyas in Pakistan have also been under such threats. The bill also excludes minority groups fleeing persecution from elsewhere, including the Rohingya Muslims of Myanmar.

So, if India cared so much about minority persecution, why not include these groups?

The controversial amendment, therefore, has not been absorbed well by the public, as there have now been protests in all twenty-nine Indian states against the policy. The student population in India it seems, has been at the forefront of the protests, the police responding with disproportionate violence.

However, it might appear that the demonstrators are not united in their motivations, as a separate unrest in response to the bill is happening in the northeastern states of India. The state of Assam for example, has had a historical battle with illegal immigration threatening the culture of its indigenous population. The protestors in regions like these are against any immigration, regardless of religion.

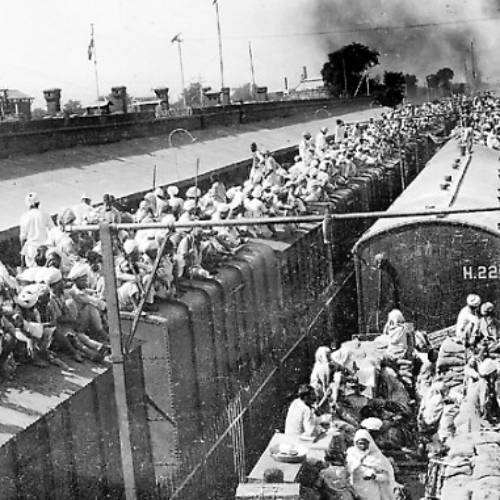

The debate around the National Citizenship Register (NRC) links to these anxieties in Assam and its relationship with the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Previously, the NRC was used to prove citizenship in Assam against the backdrop of Bangladeshi independence, which saw a migration crisis in India’s northeast. What makes this relevant, is that Hindu Bengalis, a major support base for the BJP, were left out of this list, rendering them illegal immigrants in the eyes of the law. However, now that the CAA has been passed, this group now has a road to citizenship in India, causing widespread backlash in Assam.

Assam is also one of India’s most impoverished states and a lot of its population lack the correct identification documents to prove their legal citizenship. What’s more, a major portion of the two million people left off the citizenship list in Assam are Muslim, further adding to the controversy of the group’s unfair targeting.

Indian Muslims make up for around 15% of the country’s population, and the demographic has been subject to increasing communal violence and targeting ever since the BJP won back power in 2014. It has become apparent that Prime Minister Modi has made it one of his core agendas to marginalize the group at every opportunity, whether that’s by stripping Kashmir of its internet or through building a Hindu temple on top of a Mosque that was desecrated by Hindus almost two decades ago. In November, Modi announced that the NRC would be implemented nationwide, with those not on the register at threat of being rendered stateless.

There is already a cluster of detention camps in Assam, with most of their population being Muslim, sparking outcry due to their Human Rights violations.

Anti-CAA protests have therefore continued in India at the turn of the new decade, as police have detained and arrested thousands. The government has also responded by shutting down Uttar Pradesh’s (a highly Muslim-populated state’s) internet.

Of course, the Muslim-Hindu animosity predates the rise of the BJP, but certainly their ascension to power has started a new chapter in the battle for the country’s soul, as the journey to define India as a nation continues.