My Lent-Ramadan Encounter: Fasting in Christianity and Islam

18 Mar 2020Until I started working on the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Christian-Muslim Relations Initiative in 2002, I hadn’t really encountered fasting. As I began to learn about Islam and meet Muslims, one of my early experiences was Ramadan fasting and I had to ask myself the question: ‘What is fasting, particularly, Lenten fasting, in Christianity?’

It was insightful to look into the history of my own faith, of Christians in times gone by, or in other traditions, abstaining from meat for the Lent season. I also took note of Anglicans who I worked with giving up alcohol for Lent (a longer term decision that I had already made) and a Coptic Orthodox colleague (normally vegetarian) who became vegan for Lent.

There are strong Christian fasting traditions out there. They were not particularly marked in my Methodist tradition, yet it did not surprise me to find out that John Wesley was a committed faster, or that the Moravians (his spiritual inspiration) also fasted. As a vegetarian, I could have opted for an Orthodox vegan-style Lent. But I love dairy way too much: this would be a challenge for another time. It seemed much easier as an interfaith aware Lent-fasting novice to adopt a Ramadan-style approach and not eat at all.

Of course, having tried Ramadan-lite during Lent, I then had a head start when Ramadan came around (in the autumn when I first encountered it) and I could begin to get my head (and heart and stomach) around it. For me, the characteristics of Ramadan are: fasting, reading scripture and prayer. I choose these descriptions specifically, as they fit with both Islam and Christianity. The traditional Muslim fast is to abstain from food and drink (and other things) during the hours of daylight: the fast is broken at the end of the day after sunset. This equates, in a limited way, to the historic Lent timings of fasting (in whatever manner has been chosen) during the week and then breaking it on the feast days (Sundays), strictly after receiving the Eucharist. Neither religion’s month (or longer) of fasting involves permanent fasting: it is punctuated.

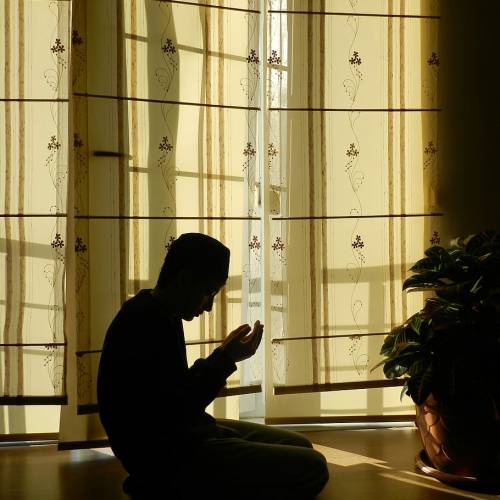

The decision not to eat frees up the mind and body to focus on other things: by not being distracted by casual snacks and endless cups of tea (when fasting with an imam friend he teased me about my tea addiction) one may hope, God willing, to be more conscious of God, and thus to be led into being more spiritual. For me, and I don’t regard myself as a hugely spiritual person, Islam has been a wake-up call in the area of personal spirituality.

Muslims believe that Ramadan is the month in which the Qur’an was first revealed and the whole Qur’an is recited in mosques during the month. I have translated this into my Lent practice by reading the Gospels (at least) and doing so while commuting, in the process ‘fasting’ from free newspapers. This ongoing process of learning about and from ‘the other’, witnessing the spirituality of Islam and then delving deeper into my own tradition, including other denominations, has taken me along paths and opened up new sights that I would never have encountered otherwise. It has added to my almost lifelong journey of wrestling with my own religion and brought unexpected blessings.

My own interaction with Ramadan, shared on social media with the hashtag #Christians4Ramadan, was one of the inspirations for a movement of Muslims joining in with #Muslims4Lent. There is joy and encouragement in seeing people of another faith enjoy and appreciate our own practices and spirituality, with sincerity and honesty, especially against a backdrop which suggests that religion is about intolerance, hatred and war.